The promise, prestige and parties of New York city has always been a beacon for aspiring writers. From Truman Capote to Scott Fitzgerald, NYC has been attracting the most talented figures in literature for well over a century, all searching for their own slice of high society inspiration. To shoot our recent New York based campaign, we dug into some of these iconic (and dapper) characters to find those writers who helped paint our romantic perception of the city with their stylish, celebrated and poetic prose.

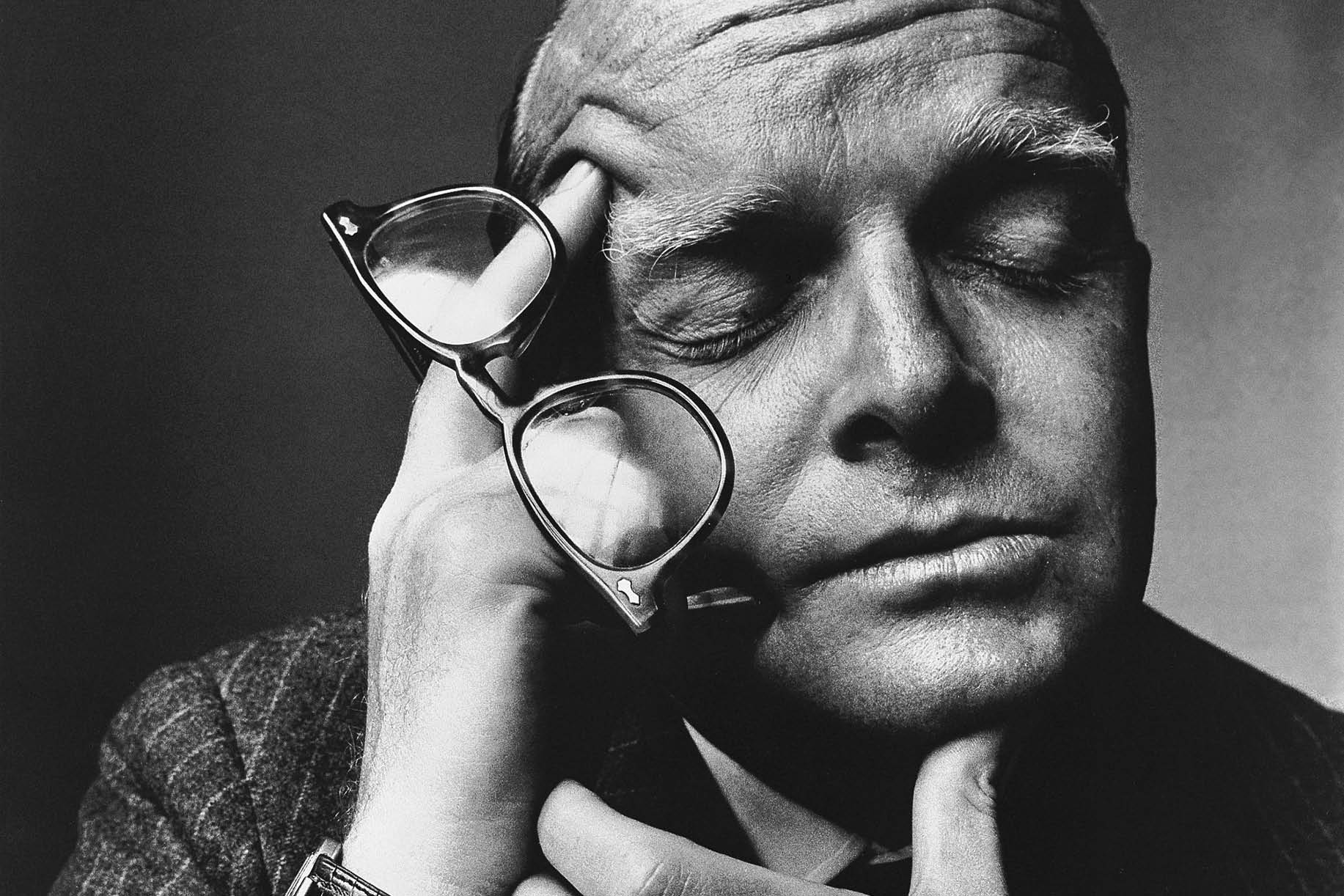

Truman Capote

‘New York is the only real city-city.’

While the celebrated writer Truman Capote grew up in Alabama, a childhood friend of fellow literary luminary Harper Lee (of ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’), it was his time in New York in the celebrity/social crowd of the 60's that embodied his greatest (and most tragic) years.

About a decade after the successful Manhattan-based novella ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s, first published in Esquire magazine, and just after his acclaimed ‘true fiction’ work ‘In Cold Blood’, his status as perhaps the world’s most known celebrity writer culminated in his hosting the 1966 ‘Black & White’ Masked Ball at the Plaza Hotel, which became famous as one of the social events of the decade.

A battle with drugs and alcohol, as well as his traumatising ostracism from New York’s elite following the book ‘Answered Prayers’, in which the fame-hungry writer fictionalised the lives of his fellow celebrities (attracting their ire in the process), led to a tragic public decline over the next two decades. His own story, like so many before and since, captured the wild possibility, prestige and vulnerability of life in high society in New York city.

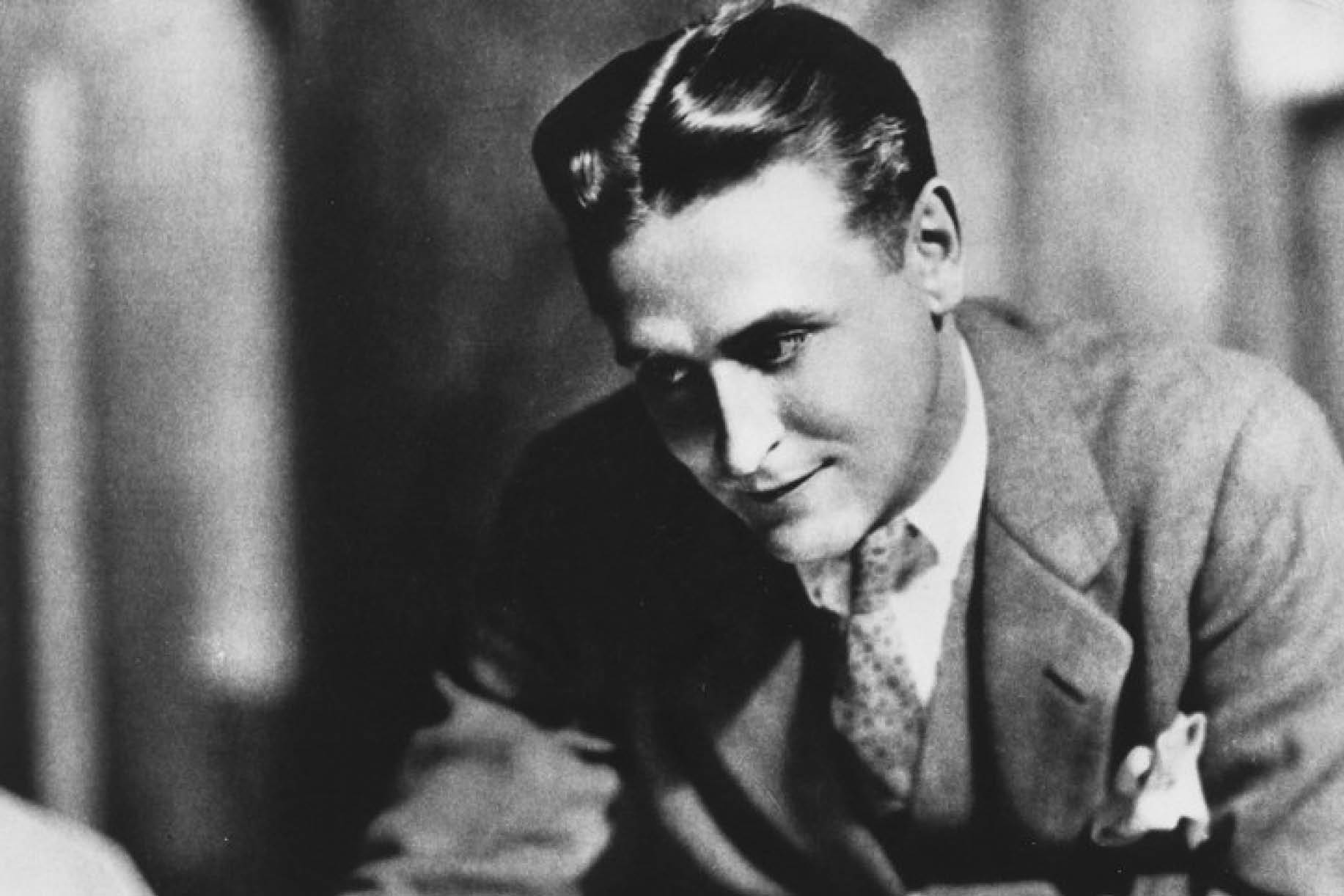

Scott Fitzgerald

‘The city seen from the Queensboro Bridge is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world.’

The iconic American author Scott Fitzgerald is widely considered one of the greats of modern times, but is also thought to have somewhat unfulfilled his prodigious talent, crafting only four complete novels in his life. His well-documented on-and-off volatile love affair with wife Zelda led the two to the forefront of the social circles of the 1920s jazz era, flitting between Manhattan, Paris, the Riviera and Hollywood. Their high-flying lifestyle was almost always above their means, despite his fame and success, and led Fitzgerald to spend most of his time writing more profitable shorter stories for magazines. It was a habit that his friend and peer Ernest Hemingway lamented publicly, lambasting Zelda as being responsible for wasting his talent.

His most well-known work, ‘The Great Gatsby’, is technically set in the ultra-wealthy conclaves within Long Island, but captures the essence of New York society at the time, conveying the utter luxury and frivolity of the Jazz Era social scene.

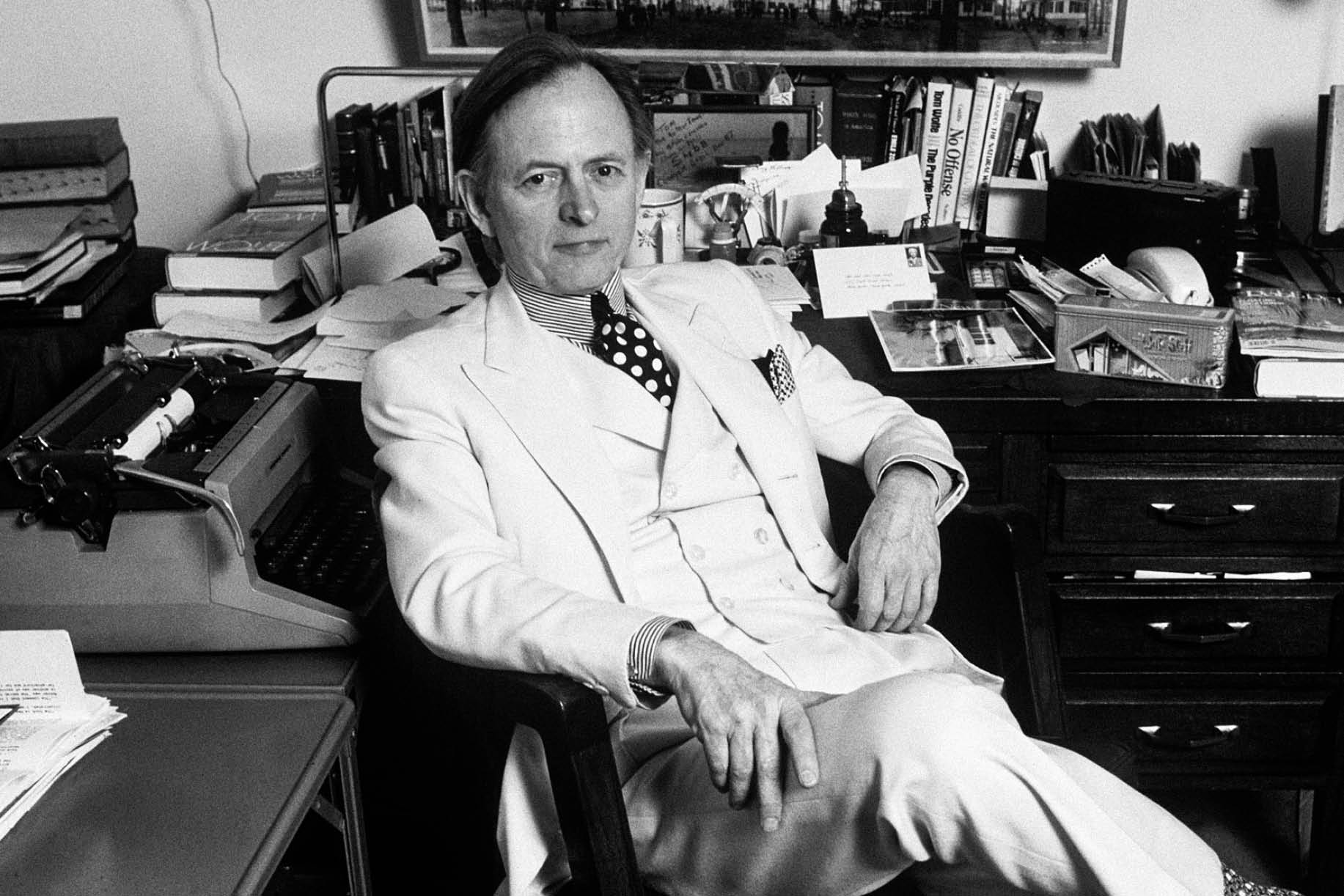

Tom Wolfe

‘One belongs to New York instantly, one belongs to it as much in five minutes as in five years’.

The American journalist, author and beloved figure of New York society was perhaps best known for advancing the style of ‘new journalism’, a type of writing that combined news reporting with more subjective literary techniques.

In the early 1960s Wolfe was engaged by Esquire to write a piece on the hot rod and custom car culture of southern California. Struggling and procrastinating on the piece, Wolfe sent his editor Byron Dobell a letter the evening before the deadline, explaining what he wanted to write in the article, but ignoring all ordinary conventions of journalism. Upon receipt his editor simply removed the ‘Dear Byron’ introduction and published the piece as is, under the title ‘There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.’ Widely polarising, the article sparked a wider conversation about the state of journalism and helped establish his writing provenance.

Wolfe’s signature style was a white suit, which he reportedly adopted in the 1960s when he purchased one to wear in the style of a southern gentleman throughout summer. Finding the fabric he’d bought was too thick for the heat, he instead opted to wear it in winter, to some public shock and ridicule, which he claimed to enjoy. Sometimes worn with a hat and two-tone shoes, Wolfe’s iconic white suit cut a familiar figure throughout New York’s literary and celebrity elite until his death in 2018.